In a post-conflict society like the Democratic Republic of Congo, jobs are scarce, enterprise minimal and expectations for professional promotion a strange concept. The country’s fledgling film industry is however changing things, allowing people to aspire, and also come to terms with a pervasive social trauma

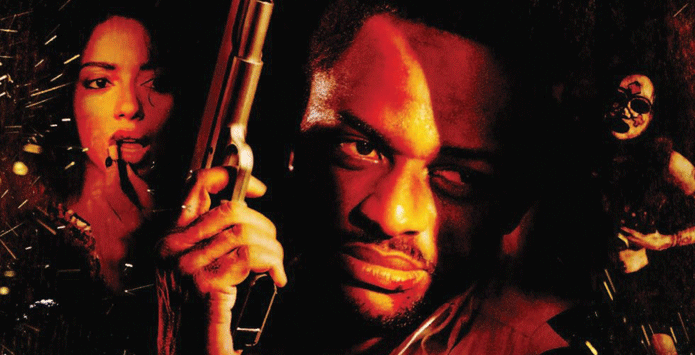

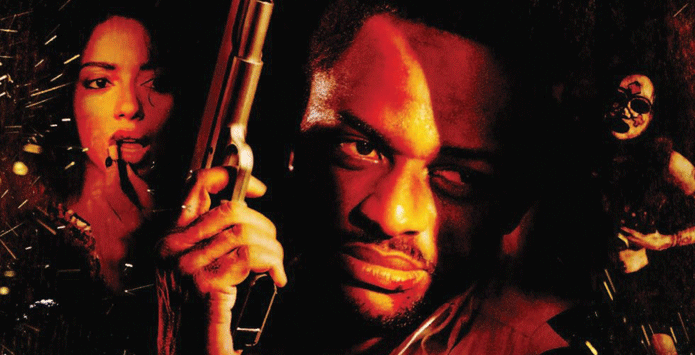

Released in 2010, the genre-based action film Viva Riva! is reputed to be the first locally produced feature film made in the Democratic Republic Congo in two decades. Written and directed by Djo Tunda wa Munga, the neo-film noir gangster flick tells of rival criminal gangs attempts to steal a secret cache of fuel. The film was set in Kinshasa, a city ravaged by years of political conflict.

“I wanted to make a film that would allow me to talk about the reality of Kinshasa, and at the same time be entertaining, but I didn’t want to do it through social-realism, the typical documentary-like style of filming when trying to ‘capture’ Africa, because that can be boring,” stated Munga in a 2011 interview with the online magazine, This is Africa.

Produced with the help of French and Belgian support, Munga, who established his production company Suka Productions! after working as a line producer on a number of foreign-made television documentaries, has likened making films in Congo, which has little to no formal infrastructure, to the criminal enterprise portrayed in his internationally successful film. “We try to find opportunities to make films, which is basically as tough as robbing a bank, but that’s what we do.”

In September last year Munga visited Johannesburg, at the invitation of the Goethe-Institut, to attend a screening of his documentary film State of Mind (2010) and talk about his filmmaking at a conference on art and social trauma, über(W)unden: Art in Troubled Times. The following is an edited version of the preparatory notes for his speech, titled ‘The Power of Art’, and is reprinted with the permission of Munga and the Goethe-Institut. The full text will be available in the forthcoming book, über(W)unden: Art in Troubled Times (Jacana, 2012).

I am from Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of Congo. I develop audiovisual training programmes for young artists, organise workshops to further the development of actors and oversee a production company, Suka Productions!, that, at times, has employed up to 60 people. Starting with nothing, in five years I put together a film crew to work on the small film television film, Papy (2009); a year later they worked on the feature film, Viva Riva! (2010), and the same crew just finished the production of a Canadian war genre film. The problems in Congo are so gigantic and complex—they are structural, psychological and metaphysical—that I am incapable of painting a fair portrait of my country in a few lines, so let me tell you instead about a young woman in her early twenties, shy and in search of work, who came by my production company one day, by chance.

As the manager, I decided to hire her based on the quality reflected in her CV. “You have a good CV,” I told her. “If you are interested, I will hire you as an intern on a documentary production. I will pay you a fixed amount for your work, and also provide a certain amount for your daily transport and food.” Her first reaction was one of amazement, then doubt. Usually, internships in Congo are not paid. At most, we offer what is called “transport”, enough to get to work and back home. It was hard for her to believe what I had just said. And yet, by international standards, this is standard practice. The young woman started working with us and proved to be a hard worker. She carried out all the tasks assigned to her, even if they were sometimes imperfectly executed.

The shortcomings of the Congolese educational system were obvious in this young woman. Its dire consequences are palpable in the way people write and speak. Unsure of their place in society, people struggle to articulate ideas and have a poor concept of what it means to produce something. In Congo, people pour a lot of energy into their work but have little idea of engaging in work that has a start point and an outcome, and of adding quality to that job. These things do not exist. Everything is engaged at the same level: doing or not doing, it does not make any real difference. There is no regard for consequences.

Some history: after the plundering that devastated the country between 1991 and 1993, the economy came to a standstill. The plundering was a mass action in which the military, followed by the population, ransacked businesses, shops, private residences, anything that had anything of value. Everything from office computers and factory machinery to doorknobs and bathrooms was looted. Try to imagine a baby placed in a large bathtub with a hundred piranhas: after a few minutes, there will be nothing left. That is what happened in Congo—the economy came to a complete standstill. I do not know if a similar case exists in modern history. In 2006, when the first elections were held after 46 years of independence, an ordinary 20-year-old Congolese would have grown up in a society where civil servants and government officials had not been paid for months, sometimes years.

As a result of all these problems Congo now imports 90% of its consumer goods. The notion of export barely exists as nothing is being produced. As a result, the notion of money as a logical consequence of work does not exist either.

By using this website you agree to our Terms and Conditions. Please accept these before using our website.