Are India's universities up to the challenge of educating the youngest population in the world?

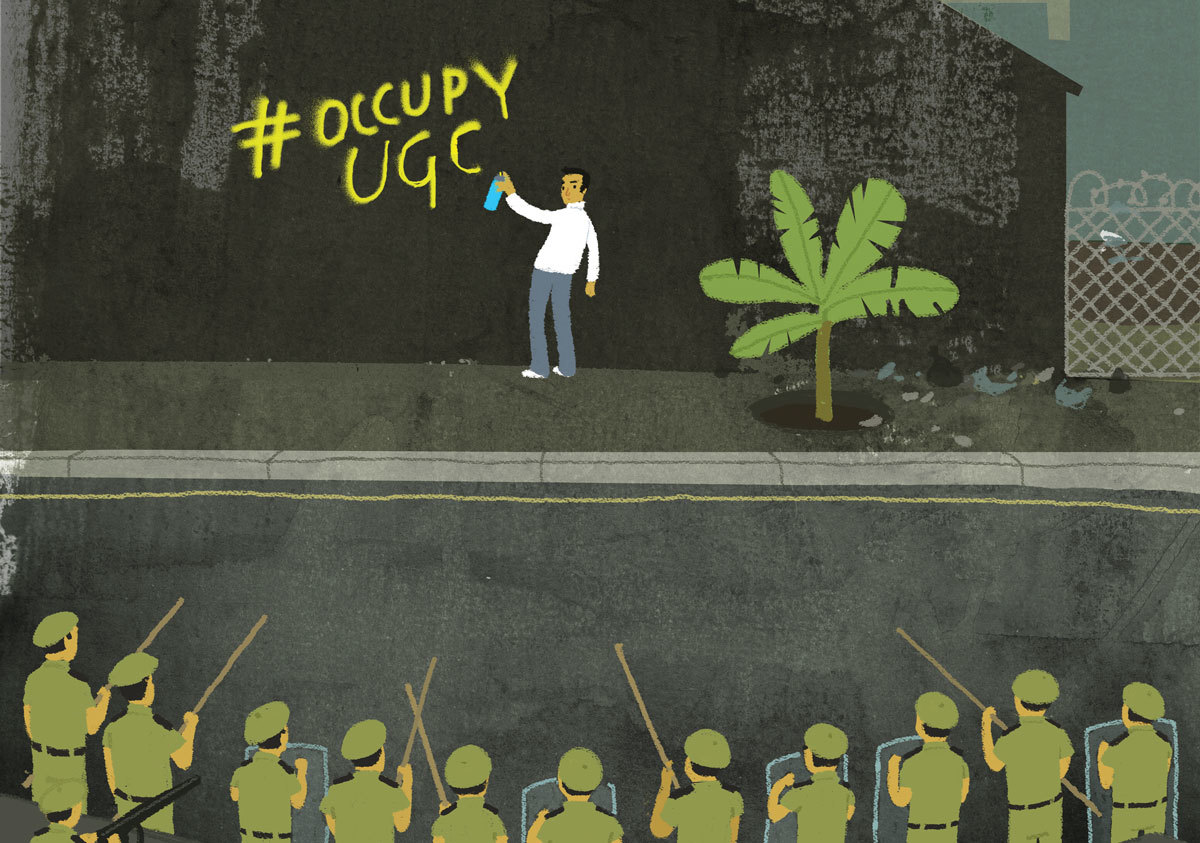

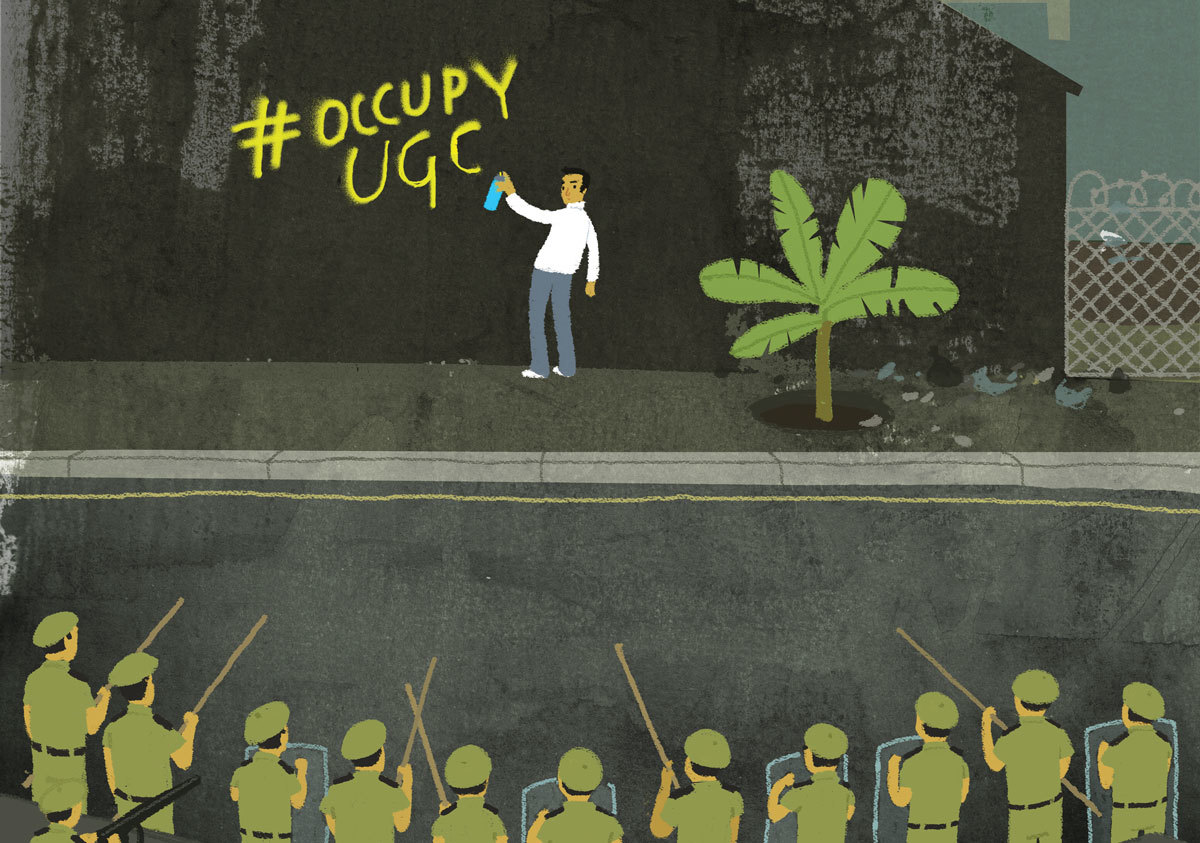

Walking past Delhi’s ITO metro station earlier this year, I was pleased to find residual graffiti for #OccupyUGC, a three-month urban occupation by research scholars motivated to think together about the threat to the political economy of higher education in India. The occupation was prompted by an administrative decision. In October 2015, the University Grants Commission (UGC) at Delhi—a central body that maintains and disburses funds for higher education—decided to roll back funds for scholarships to doctoral research students. The decision directly affected an already tenuous economy.

Doctoral research in India varies across the liberal arts and sciences, with gradations of scholarships contingent upon the location of scholars in central or state universities. Students are vetted by a standardised exam known as the National Entrance Test (NET). Given the nature of this exam, a substantive scholarship is often out of reach and doctoral students must negotiate a subsistence economy that relies on stipends mandated for those who do not fare sufficiently on the NET exam. Instituted in 2005, the stipend system notionally offers a living wage for intellectual work.

But without money for hostels, living expenses and reading materials, higher education is simply inaccessible to most aspiring students.

In 2015, a review committee appointed by the government, which is on a drive to increase institutes focussed on technology, management and the technical sciences, decided that 35,000 liberal arts scholars did not need money to study. The living-wage scholarship was reduced to a meagre sum of US$75-125, nearly half the minimum wage for semi-skilled labour. Rather unhelpfully, a member of parliament justified this move by stating that students used the money for shopping, not study. The claim did not endear him to the many students affected by this decision. However, the Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD), formerly Ministry of Education, concurred with the parliamentarian’s assessment: in October 2015 it said it was concerned about the “irresponsible” use of scholarships.

The living-wage scholarship was reduced to a meagre sum of US$75-125, nearly half the minimum wage for semi-skilled labour

Student protests followed, and were met with heavy-handed police action, including the use of long wooden batons known as lathis. Students responded by establishing a camp on the lawns of the UGC building, located at the intersection of Delhi’s old city and the unfurling postcolonial city with buildings of the press, income tax office, museums and Supreme Court. The action also generated a hashtag: #OccupyUGC. The occupation movement comprised a loose body of unaffiliated researchers who had come together to think about the structure of higher education. Their disaffection was summarised in a graffiti statement: “We are students, not customers.”

Students from across the country began to show up at UGC. At the heart of their demand was the desire to study. The threat that India’s higher education might be privatised loomed large over the occupation: the country was poised to pledge its higher education to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATTs) at a December meeting of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in Nairobi, Kenya.

The occupy movement benefited from its urban setting, with roadside restaurants known locally as dhaba offering convenient luncheon spots. A nearby mosque took an active interest in the students and as Delhi grew wintry ensured a constant supply of tea and weekly helping of biryani; it also offered clean toilets and a safe-haven during police charges. While the streets were generally friendly, the authorities were not. The occupation prompted constant provocation, sometimes by proxies—mostly rowdy men on motorbikes—but often directly by lathi-wielding police accompanied by right-wing student groups.

Threatened with displacement, the students found legitimacy by simply digging in. “The idea of occupying a city became a powerful idea,” says Avipsha Das, a doctoral student and social-media manager of the struggle. As the occupation continued, its participants organised open classrooms with faculty from universities across Delhi, cultural programmes that included song and dance, and nocturnal vigils and discussions. By the end of October, a key topic of discussion was the pending WTO-GATTS conference in Nairobi. A new slogan showed up on the walls of the Delhi metro: “Education had a value, and now it has a price”.

Full article available on login

Kavya Murthy is a Delhi based researcher and writer

By using this website you agree to our Terms and Conditions. Please accept these before using our website.