A beacon for regional solidarity and critical thought for more than a quarter century, the Nepal-based magazine Himal Southasian abruptly stopped printing in late 2016

Print journalism is fighting for survival everywhere. The story of Himal Southasian, whose operations from Kathmandu was suspended in November 2016, is a tale of how independent long-form journalism has had to shape-shift in the face of rapid economic and political transformations over the last three decades in order to survive in a competitive market-driven media industry. Founded in May 1987 as a magazine for “environment and development” by Nepali editor and writer Kanak Mani Dixit, the editorial in the first issue—or “prototype” as Dixit called it—set forth the agenda. Himal was to be “an independent and unofficial forum to facilitate constructive dialogue among individuals engaged in Himalayan development”.

Spread across Bhutan, India, Nepal, China and Pakistan, the Himalayan mountain range has given these countries in the northern region of the subcontinent a shared border. Himal’s key interest in this early phase lay in “furthering communications between one Himalayan valley and the next,” and to cover issues pertaining to “population, migration, family life, agriculture, industry, conservation, wildlife, mountaineering, forestry [and] tourism”. The magazine was initially pitched at a “sample target audience, advertisers and prospective funders,” until advertisers and subscribers would set the ball rolling. The magazine was published in English, an interesting strategy in a multi-lingual region at a time when the English-language media was not as ubiquitous and powerful as it is now.

Conceived by Dixit in New York, the printing and design of the magazine was handled in the

Sri Lankan capital of Colombo as Nepal did not have the necessary resources at the time. Himal later shifted its base of operations to Kathmandu, a multi-ethnic urban agglomeration of five million in the Kathmandu Valley, that enabled the kind of pan-regionalism the magazine came to represent. The location in the capital of Nepal was convenient because the city allowed for relatively freer movement of citizens of different nationalities in the region to enter and mingle. On the other hand, visa regimes in India and Pakistan are famously difficult to negotiate, making cross-border movement of people extremely restrictive. From its base in Kathmandu, Himal suggested the possibility of a genuine alternative to the dominance of India and Pakistan in defining “southasian-ness”.

Initially published a bi-monthly and known simply as Himal, in 1996 it shifted to a monthly cycle with an adapted masthead that included the word “South Asian” (later “Southasian”) in its title. Its editorial focus also shifted from a tight focus on the Himalaya region to encompass the regions of Afghanistan to Burma and Tibet to the Maldives. The magazine had by this time developed a biting and satirical style. Often polemical, it gathered a steady stream of well-known and influential contributors and a growing list of subscribers. At its peak, Himal was the only South Asian publication that enjoyed steady contributions from writers, intellectuals and journalists from across the region, including Bangladesh, Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka, Burma and the Maldives.

Himal managed to prosper for 30 years. Its demise directly keys into political shifts in the great region it covered

“An imprecise, but very South Asian identity extends from Sri Lanka’s coconut plantations to the Nepali mid-hills, and from Manipur’s jungles to the rugged Baluchi terrain. Afghanistan, the Tibetan plateau and Burma, too, are more part of this region than any other,” offered Himal in its first. Its contributing editors expanded to include contributors from Dhaka, Colombo, Lahore and New Delhi. Himal’s covered a wide range of topics, including politics, sports, literature and urban issues. The magazine continuously returned to the subject of the South Asian city under neoliberalism.

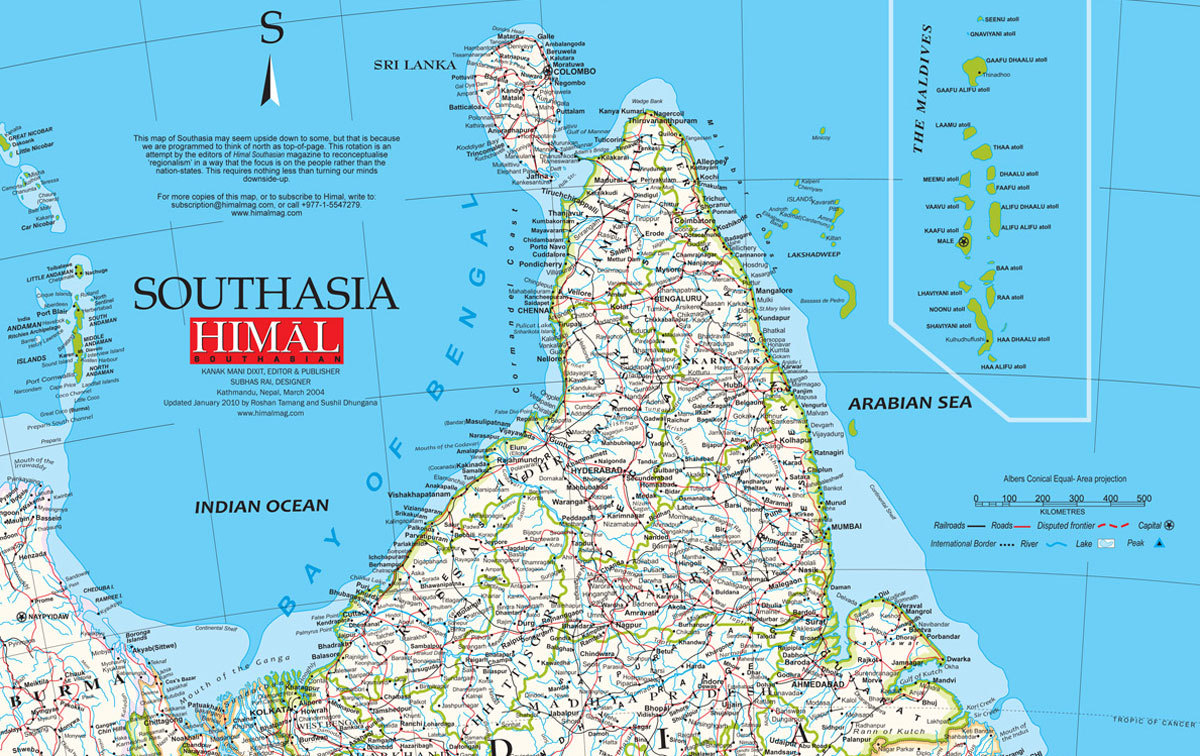

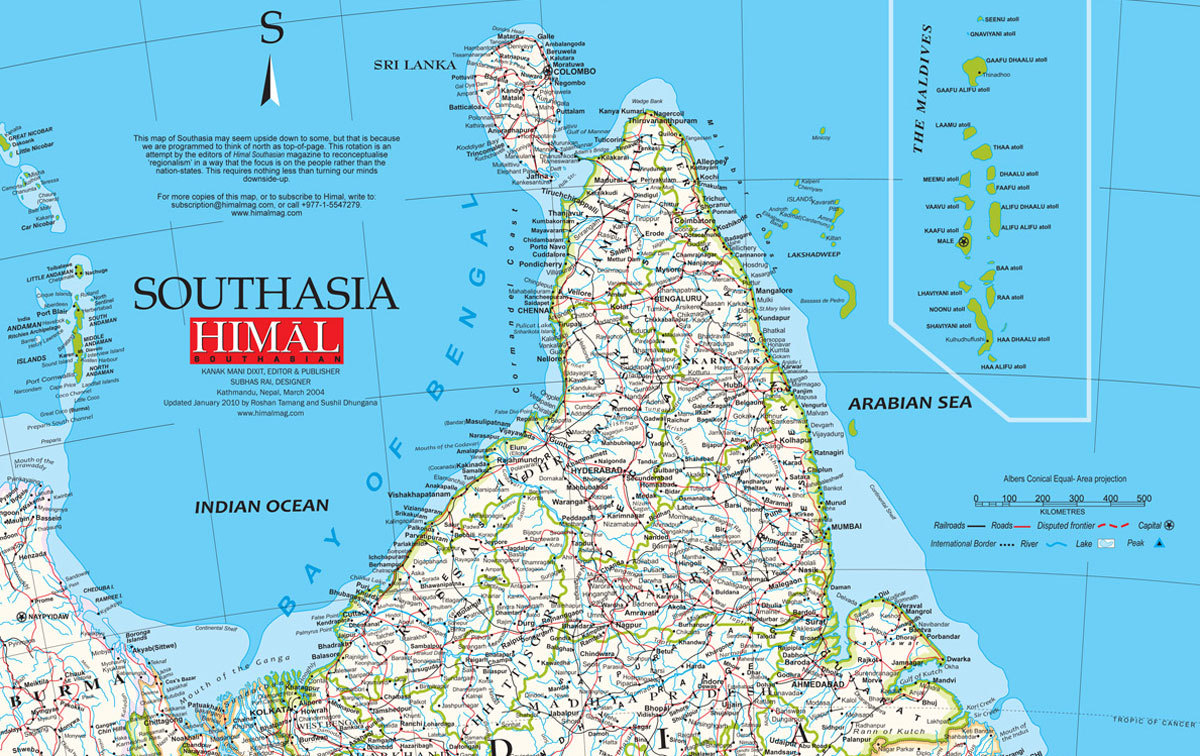

Himal purposefully attempted to steer clear of a naïve sense of “southasian-ness”; it also rejected cynicism about such a project. In January 2002, Himal published an inverted map of the subcontinent on its cover. Designed by the Kathmandu artist Subhas Rai, the map showed Sri Lanka on the top and south India at the centre. It became a trademark image associated with the magazine. Rai’s graphic clarified the underlying impulse that guided the magazine in its editorial ambitions until its end. The January 2002 included excerpts from roundtable talks organized by Himal in November 2001 to coincide with the 11th South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) Summit in Kathmandu. Among other things, the roundtable interrogated the idea of South Asia and regionalism itself, and the difficulties it presented.

Discourse on modern-day South Asia has largely been determined by the history of the 1947 Partition of India, a moment that signalled the formation of independent nation states following an anti-colonial movement that overthrew the British Raj. The period unleashed the trauma of civil war and the largest mass migration of people in history. Partition not only saw the drawing of geographical boundaries along the Radcliffe line between India and Pakistan (and later India and Bangladesh), it inadvertently produced a framework for how to think of the region. Himal sought to break out of this mould, providing an early imperative to think through a regional perspective, while critically interrogating the bilateral partnerships that occurred under the aegis of a global neoliberal economic restructuring.

Full article available on login

Puja Sen is a journalist based in Kathmandu

By using this website you agree to our Terms and Conditions. Please accept these before using our website.