Franco, the godfather of Congolese Rumba, wrote the soundtrack to Africa’s early post-independence years. He skilfully negotiated change and tyranny in Zaire with guitar and song

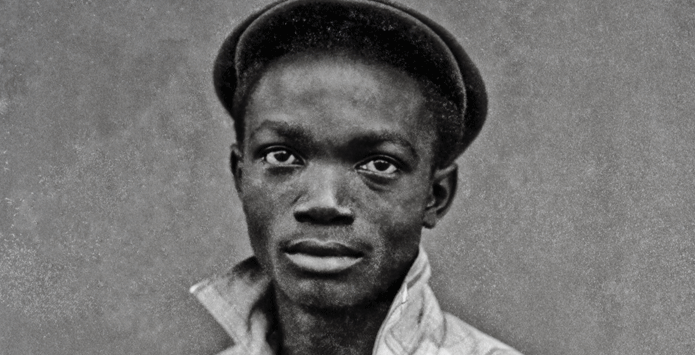

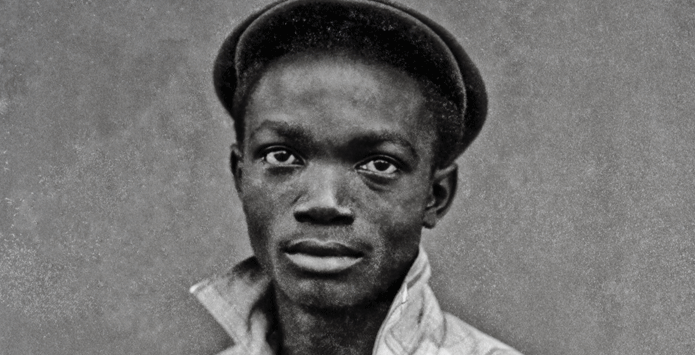

Maybe it’s best to start with some personal reminiscing. The year was 1986, and I had lived in the Kenyan capital Nairobi for about a year, and now finally I had the privilege to see one of Africa’s biggest stars perform live: the mighty, colossal Grande Maître of Zairian music. The man who had been nicknamed Yorgho (Godfather) and Sorcerer. The man who after his death in 1989 would be honoured as Commander of the Order of the Leopard. His name was Franco.

‘Franco’ meant nothing to me when I arrived in Nairobi in September 1985. In fact, apart from the usual names of King Sunny Adé, Fela Kuti and Osibisa, I didn’t know or care much for African music. I had grown up on a steady diet of Bob Dylan, Rolling Stones and The Clash, anything that had loud guitars and snotty vocals. But that would soon change.

The first couple of months we stayed in the Chiromo Hotel, which must have been a chic place in the 1970s—but not anymore. It had turned into a quasi-nightclub with a resident band. Since the music was too loud to sleep I often wandered down from my room to watch them. Every cliché about African night life was true. The place was sweaty and packed with prostitutes and men looking for pleasure. The beers were huge. The music was pumping and the bodies shaking. But what did surprise me was that the sound of this band reminded me much more of Latin America than Africa. I had expected drums, horns and chants. Instead I heard liquid guitar lines, subtle rhythms and sweet vocal harmonies that had very little in common with Fela Kuti’s rants against tyrants. It was also the first time I saw someone play the Fanta bottle as a percussion instrument, stroking the glass ribs with a hard object.

After one of the shows I chatted with the musicians, who told me they mainly played music from Zaïre, now the Democratic Republic of Congo. I scribbled down some names: Tabu Ley, Mbilia Bel, Sam Mangwana, Super Mazembe, Zaiko Langa Langa, Franco. From then on it was a magic trip of discovery. This jubilant music—known as rumba, or soukous, from the French word secousse, shake—was everywhere. It came blasting in grand distorted fashion from matatus, the overloaded public taxis. You heard it in the bars in Tom Mboya Street. And it resonated through River Road, the lively, sleazy street at the bottom of town where you would find rough ‘n ready recording studios.

Franco was the ultimate global pop phenomenon. He was a band leader in the grand tradition of Duke Ellington and a proper guitar hero; his music was as sexy as that of James Brown; his lifestyle matched that of Mick Jagger; he was a precursor to Jay-Z and Kanye West; and he fitted right in with avant-garde dance pop of the early 1980s

Soon I began to recognise the structure: a slow section, a bit with duelling guitars, the sebene, and then the fast section with huge waves of brass, chiming guitars and hefty vocal choruses. Just like garage rock the songs were usually built on two or three basic chords. The euphoric, orgiastic effect of the tempo change can be compared to early house music where the dancers, arms in the air, are waiting for the DJ to drop that beat again. But here the drug was beer, not ecstacy.

What made this trip of discovery especially rewarding was that you had to rethink and reset your preconceived ideas of good and bad, hip and square. In Nairobi in the mid-80s The Clash weren’t cool, neither were Prince or Madonna. Instead you encountered a whole different set of African pop stars with names like Sam Mangwana, Vijana Jazz and Shirati Jazz. Even that word jazz was misleading. This music had nothing to do with jazz as we knew it. You didn’t hear the influences of Brubeck, Davis or Coltrane. But it was jazz, in the sense that it made use of syncopated rhythms and melodies. And conceptually it was similar to the original New Orleans jazz: ecstatic urban dance music.

Franco was my favourite. If his main rival Tabu Ley was the Frank Sinatra of Africa then Franco could be likened to Elvis Presley. His style was less smooth and his baritone sounded more gravelly than the honeycomb voice of Tabu Ley. As Franco connoisseur Ted Braun wrote in the extensive liner notes of the excellent Franco compilations Francophone Vol. 1 and Vol. 2: “His voice wasn’t pretty, but it caught the ear. His vocal range was limited but his emotional range was great.”

By the time I came across Franco he had been on the scene for over 30 years. The secret of his success was that, apart from being an outstanding singer, guitarist and songwriter, he also had a nifty eye for talent, always assembling a new gang of gifted musicians and singers around him. Over the years over a hundred of them passed through his ranks. Playing in his TPOK Jazz band was a guaranteed ticket to success. Or as New York music critic Robert Christgau put it: “He did his damnedest to hire underlings who were even better at singing and writing than he was.”

Franco was the ultimate global pop phenomenon. He was a band leader in the grand tradition of Duke Ellington and a proper guitar hero; his music was as sexy as that of James Brown; his lifestyle matched that of Mick Jagger; he was a precursor to Jay-Z and Kanye West; and he fitted right in with avant-garde dance pop of the early 1980s. In order to explain all that, a proper assessment of Franco’s life, music and career is called for.

François Luambo Makiadi was born in 1938 the village of Sona Bata in Bas-Zaïre, in what was then Belgian Congo. He was still an infant when the family moved to the capital Leopoldville, where his mother had a stall at the Ngiri Ngiri market. He was only 11 when his father died and he had to leave school. Using a self-built guitar, a harmonica and a kazoo, young François tried to attract customers to his mother’s stall. His guitar playing was noticed by a fellow young musician Paul “Dewayon” Ebongo, who invited him to his band Watam, the Delinquents. One of the first songs the band recorded in 1953 was ‘Esengo Ya Mokili’. Its chorus wouldn’t seem out of place on an early hiphop record: “What a pleasure in this world to be famous!”

Young François was soon discovered by an older rumba musician, Henri Bowane, who added the 15-year old boy to his band and christened him “Franco”. It was Bowane who taught him the sebene, the bit where the three or four guitars improvise. Franco progressed from second to first guitar, perfecting his trademark style which depended on the use of thumb and forefinger, eschewing the plectrum. Even on his very early recordings we can already hear his quicksilver sound, pushing and stroking the song, caressing the melody, lifting it above mediocrity. Music critics have likened his sparkling quicksilver lines to those of Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia, while his sense of rhythm has been compared to Bo Diddley.

In 1956 he co-founded OK Jazz, the band that would become synonymous with Franco until his death in 1989. The group was named after the OK Bar—owned by O(scar) K(ashama)—where they were the resident band. They played Cuban derived rumba. The sounds of Cuba, which themselves had African slave roots, had become popular on Congolese radio in the 1940s. But the African musicians had given it their own twist, using electric instruments and changing the beats somewhat. Cuban music had become synonymous with an exotic modernity in a country that was rapidly industrialising and moving toward independence. The OK Bar attracted an eclectic crowd, ranging from intellectuals and businessmen to dockworkers and prostitutes. This was the first generation of Congolese that had largely grown up in the city. They were the new hipsters, who looked down on the rural folk and their traditional ways. They spoke Lingala, the ever developing lingua franca: lively, sharp and occasionally vulgar. Franco, who mainly sang in Lingala, became their voice, with his tales of modern life, his songs about love and betrayal and the lives of the common man.

In 1960, when Franco was 22, Congo gained its independence; it was the same year he became the de facto leader of OK Jazz, after the departure of co-founder Vicky Longomba. By this time the band had grown to 14 instrumentalists and half-dozen singers. The OK Bar was perennially pumping. TPOK Jazz’s signature song from 1957 was ‘On entre OK, on sort KO’ (“you enter okay, you leave knocked out”), which summed up a steamy night with the orchestra. Meanwhile the tall, handsome, sharply dressed Franco became the man about town, confident and cool, riding a Vespa scooter and showing off the latest European styles. His stature was comparable to some of the early hiphop stars: rebellious, urbane and cheeky, with a love for money. His music would be the soundtrack for the new country, which, like the rest of post-independence Africa, aspired to be cosmopolitan, confident and suave. Congo around 1960 was a country full of optimism.

That wouldn’t last. Turbulent times started with the ousting and eventual CIA assisted execution of socialist Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba in 1961. The political uncertainty would continue for four more years and ended with a coup d’état by Mobutu Sese Seko, who in 1971 embarked upon a process of Africanisation. The country would henceforth be called Zaïre, while the capital would be known as Kinshasa. Meanwhile the band had also changed its name to TPOK Jazz, tout puissant, “almighty”.

Hand in hand with the political changes the focus of Franco’s lyrics shifted. He started to tackle the social problems that resulted from the fast urbanisation. On ‘Bato ya Mabe Batondi Mboka’ (1964) he was at his most outspoken when he sang: “Bad people fill this country, schemers fill this country/ They lay traps for their allies/ Only later will we ask how they succeeded.” Two years later he recorded ‘Luvumbu ndoki’, a song about political assassinations. The authorities weren’t happy and had every copy of the record destroyed; Franco and his bandmates were also forced to temporarily flee across the river to Congo-Brazzaville. From then on Franco would refrain from using overtly political lyrics. But he turned out to be a master in mbwakela, the art of hidden meaning, using allegories, metaphors, vernacular, fables and folk tales. People keenly listened to every song, dissecting it for hidden messages. Could a reference to slaughtered bush meat be read as a bleeding young virgin?

Full article available on login

Fred de Vries is a South African based Dutch writer and journalist

By using this website you agree to our Terms and Conditions. Please accept these before using our website.