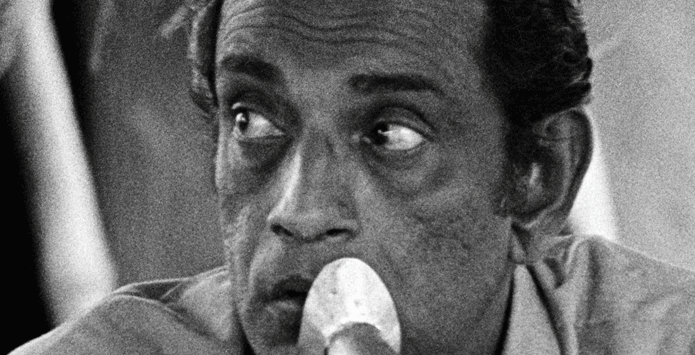

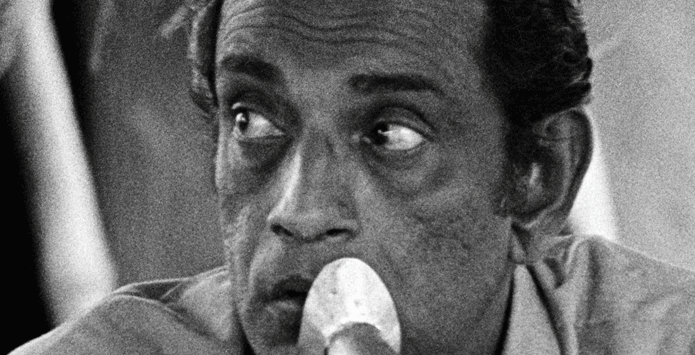

Satyajit Ray was a complex and contradictory figure, but in his capacity to engage with the inner lives of many different types of people and to find the right expression for them he has emerged as one of cinema’s most universally appealing directors

The tall man is moving about a cluttered room, monitoring elements of set design while his film crew get their equipment in place. He asks an actor to try a rehearsal without his false moustache, and continues to joke and banter for a few seconds. Whether speaking English or Bengali, his mother tongue, the man’s delivery remains casually fluid. Quickly, he shifts back into the meter of the sombre professional, the father figure keeping a close watch on things. He sits on the floor at an uncomfortable, slanted angle and looks through the viewfinder of the bulky camera, placing a cloth over his head to shut out peripheral light. This scene from Shyam Benegal’s 1985 documentary about Indian filmmaker Satyajit Ray’s life and career is memorable and absurd: Ray is so unusually tall that, crouched on the floor with his equipment, surrounded by assistants, he resembles Santa Claus examining the underside of his sleigh, circled by his elves.

Satyajit Ray was an auteur in the most precise sense of that often-overused word. Apart from directing, he wrote most of the screenplays of his movies—some adapted from existing literary works, others from his own stories. He also composed music, drew detailed, artistic storyboards for sequences, designed costumes and promotional posters, and occasionally wielded the camera. Above all, he brought his gently intelligent sensibility and a deep-rooted interest in people to nearly everything he did. He was, to take recourse to a cliché with much truth in it, a culmination of what has become known as the Bengali intellectual Renaissance.

The Indian state of West Bengal, from which Ray hailed, has long been associated with capacious scholarship and a well-rounded cultural education. The towering figure in modern Bengali history—certainly the one most well-known outside India—was the Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore, a multitalented writer, artist and song composer; as a young man in the early 1940s, Ray studied art at Shantiniketan, the pastoral university established by Tagore, but this was just one episode in his cultural flowering. Ray was born in 1921 into a family well-steeped in the intellectual life: his grandfather, Upendrakishore (a contemporary and friend of Tagore), was a leading writer, printer, composer and a pioneer of modern block-making; his father, Sukumar Ray, was a renowned illustrator and practitioner of nonsense verse whose work has delighted generations of young Bengalis (and now, increasingly through translation, young Indians across the country).

From this fecund soil emerged a sensibility so broad that it defies categorisation. If cinema had not struck the young Satyajit’s fancy— he was an enthusiast of Hollywood movies, interested initially in the stars and later in the directors—he might have made an honourable career in many other disciplines. He worked as a visualiser in an advertising agency and as a book cover designer before embarking on his film career, and even today people who are familiar only with one aspect of his creative life are astonished to discover his many other talents. And for this reason, a useful way of looking at Ray is through the prism of the narrow perceptions that have sometimes been used to define or pigeonhole him. These usually come from those who are only familiar with his work in fragments: viewers from outside India, as well as non-Bengali Indians who may have seen only a few of his films.

Simplistic labels have been imposed on him ever since his debut feature Pather Panchali (Song of the Little Road, 1955) came to international attention at the 1956 Cannes Film Festival where it was awarded a special mention. Based on a celebrated 19th century novel by Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyaya, this subtle, deeply moving film is about a family of impoverished villagers, including a little boy named Apu, who would become the protagonist of the celebrated Apu Trilogy – travelling to Calcutta as an adolescent in Ray’s next film Aparajito (The Unvanquished, 1956) and finally coming of age in Apur Sansar (The World of Apu, 1959). Though Pather Panchali is rightly regarded a milestone in the history of Indian cinema, it was also the subject of misunderstandings among those who were not yet accustomed to dealing with directors and movies from India. In a perceptive essay about a later Ray film Devi (The Goddess, 1960), the American critic Pauline Kael (of The New Yorker fame) noted that some early Western reviewers had mistakenly believed Ray was a “primitive artist” and that Apu’s progress over the three films in some way represented the director’s own journey from rural to city life. Indeed, the critic Dwight Macdonald wrote of Apur Sansar that while Ray handled village life well enough, he was “not up to” telling the story of a young writer in a city, which is “a more complex theme” —the implication being that rural stories were somehow truer both to Ray’s own life experience and to the Indian condition in general.

Full article available on login

Jai Arjun Singh is a New Delhi-based writer and journalist. His book about the 1983 Hindi film Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro was published by HarperCollins in 2010.

By using this website you agree to our Terms and Conditions. Please accept these before using our website.