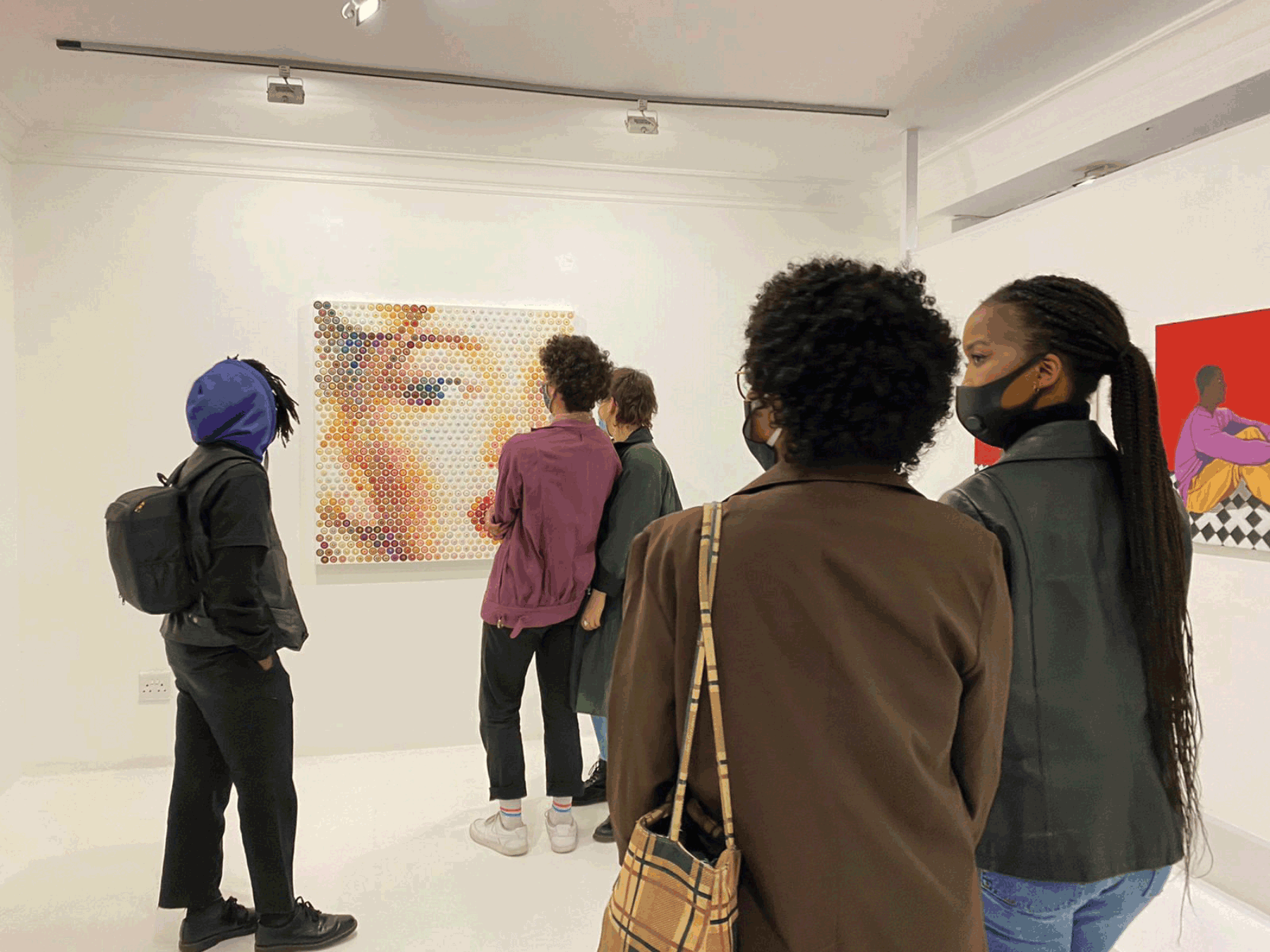

Photo by Jodi Russell

A fearful future

Cape Town’s art scene fumbles its way through a series of lockdowns

13 Aug, 2020 | Updated 02 Jul, 2021

It was February 2020, the peak of Cape Town summer, and the Mother City was abuzz with an eclectic range of arts events. A visitor could drop in to the Investec Cape Town Art Fair, the largest annual fine arts event of the season, located at the Cape Town International Convention Centre. Alternatively, one could head to the Winelands for the first Stellenbosch Triennale, taking place in its namesake colonial university town, also home to some of the country’s wealthiest individuals. Punters were spoilt for choice. As the month progressed, however, the gravity of Covid-19, till then something merely happening elsewhere, became a grim reality.

South Africa’s descent into the pandemic was swift. The first case was reported on March 5. By March 27th, the country’s government, following many others, imposed a lockdown that began at Level 5—one of the world’s most restrictive stay-at-home measures implemented.

All public life beyond that deemed essential came to a halt. The city’s vibrant art sector came to a standstill. As with many people worldwide, Capetonians initially embraced the novelty of the government’s stay-at-home restrictions. But soon the welcome break from the preceding period of back-to-back arts events gave way to an eerie stasis.

As the country groped its way through the various stages of lockdown that would define 2020, the impact of the Covid-related restrictions on the arts came painfully into focus. Questions about the sustainability of galleries and other cultural venues across the city emerged. With little government support for the industry, especially amid the spectre of other struggling businesses, it was unclear what of the scene would survive. Conversations about the value and need for art in a city that ranks highly as one of the most unequal worldwide became de rigueur among the arterati.

"INSERT MOBILE SIDEMENU HERE"

Importantly, the economic value of the country’s cultural sector became a key talking point too. Relative to the 7% of the nation’s workforce employed in the sector before the massive job losses that came with the pandemic, the government’s ZAR150 million (about $10 million) rescue package for the cultural and creative sector was simply inadequate. Important cultural institutions like the famed Fugard Theatre folded amid multiple headlines. Smaller, lesser-known spaces, lacking the Fugard’s clout, just faded away.

But, in some cases, the soul-searching and anxiety resulted in exciting experiments. In the absence of physical exhibitions, opening nights, and other standard practices, artists shifted to the digital realm. Online platforms earlier conceived of as being in service to their brick and mortar counterparts suddenly became the go-to spaces to view, trade, and exchange ideas about art and culture. They also became spaces to share tactics and resources to help artists and arts organisations survive

the pandemic. Resource lists circulated, online events cropped up. One year on, these shifts continue.

A survey of the world wide web beyond Cape Town shows some captivating ingenuity in this terrain. That said, to date, nothing truly evolutionary has emerged out of the city’s often surprisingly inventive art scene. Our digital realm still feels like an empty gallery, quietly awaiting its moment

to shine.

The month of February, typically the buzziest and busiest time in Cape Town, remained quiet this year. The big Art Fairs that usually kick off the year, making lots of money for gallerists and artists, and all the accompanying networking activity were all postponed. The usual throngs of international tourists who flood the galleries didn’t even make it to our borders. Heading into winter, we wait to see what the reaper leaves behind and what changes stick.