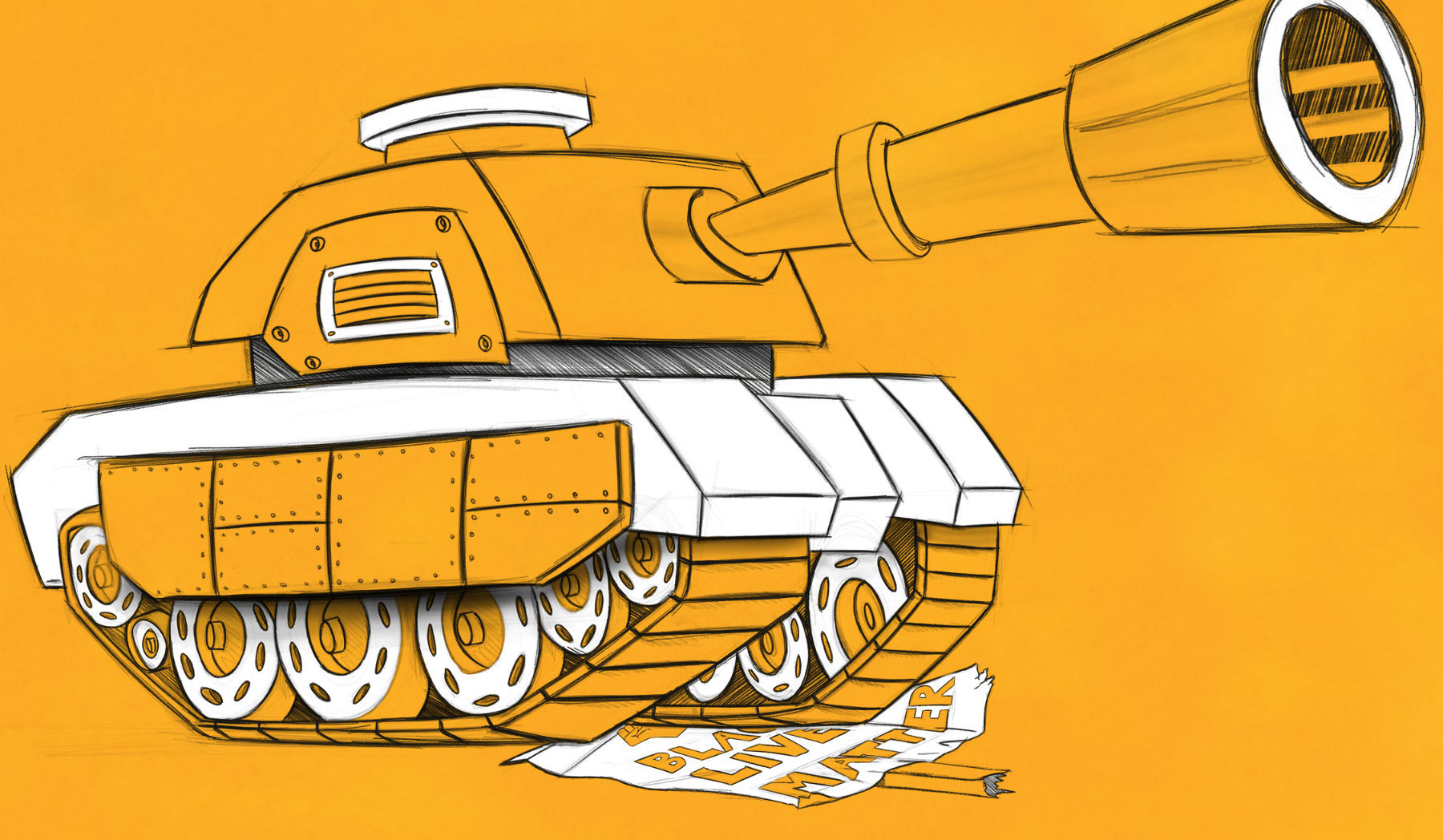

Illustration by Blain van Rooyen / Cityscapes

Communities can protect themselves

Block Clubs can empower citizens to take more responsibility for watching over their communities

13 Aug, 2020 | Updated 09 Jul, 2021

When I stepped out of my home on Chicago’s West Side in late May 2020, my brain struggled to process the scene in front of me. Military tanks lined Madison Street. Soldiers in military fatigues stood in front of buildings; some patrolled the block. Broken glass, half boarded-up storefronts and debris from days of uprisings evinced the anger following the murder of George Floyd, a 47-year-old Black man killed by a Minnesota police officer. In a video filmed by a teenage bystander, Floyd was restrained and struggling for his life.

According to a recent study by The Guardian, Black men between the ages of 15 and 34 are nine times more likely to be killed by cops in America than any other Americans.

The image of armed soldiers on the streets of a prominent American city did not evoke a sense of safety—only dread. Communities—especially those long-forgotten—simmered with an anger pent-up through countless incidents in which Black people have died at the hands of American police.

Police scrambled to restore some order, even as they perpetuated disorder in some places. All notions of “safety” seemed suspended—until further notice.

Soon after Floyd’s killing, another video of police murdering a young man emerged online. It, too, sparked massive protests. This time, in Nigeria.

On the 3rd of October 2020, in Ughelli, a town about 450km from Lagos in Nigeria’s Delta State, a bystander captured a video of the notorious Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) officers shooting a man dead before driving off in his vehicle.

Created in 1984 in response to a rising number of armed robberies, kidnappings and other violent crime, it didn’t take long for this elite crime-fighting unit to become the object of dread. Members took part in extrajudicial killings, corruption, and routinely flouted regulations. SARS also systematically targeted young men. In their warped logic, having a tattoo or wearing earrings were signs of gang membership. Similarly, possessing an iPhone was a clear sign of involvement in illegal activity —only criminals could afford them. This resulted in sometimes deadly encounters and multiple cases of abuse.

In an attempt to kill the story of the killing in Ughelli, police claimed the video was fake and arrested Prince Nicholas Makolomi, the videographer who filmed and posted the incident online. This move incited the #EndSARS protests, which quickly spread across Nigeria and sparked solidarity protests worldwide.

Nigeria’s police forces were formed during the country’s colonial era and are still generally regarded with suspicion. Marginalised and poor communities see the police’s primary duty as furthering state interests above all else.

The origins of policing in the United States are similarly steeped in the country’s original sin—created to protect private property, including capturing escaped Black enslaved people. Wariness and mistrust of the police, mostly among communities of colour, is warranted and logical and necessary.

2020 ended as one of the United States’ most violent years in decades as cities—both big and small—reported astronomical increases in murders. A 2020 report released by the Council on Criminal Justice recorded a rise in homicides by a daunting 8% between 2019 and 2020. The continued increase in documented police brutality led to heightened demand for reforming policing and a rethink of intercommunal safety across the United States.

One cannot assign a one-size-fits-all approach to community safety for cities across the world. The Nigerian context is different from that of the US. However, what is constant is the importance of hyper-local models of organising, which are unsurpassed in their ability to create networks of care and accountability for community members. Member accountability to each other, first and foremost, and each other against the state, is critical.

Hyper-local community safety models are premised on the notion that safety is based upon trust and that trust is a byproduct of intentional relationship-building. This intentional relationship-building is critical to establish a community fabric upon which to build a culture of care.

The Block Clubs we are helping activate in South and Westside neighbourhoods like Bronzeville and Austin adopt this model. Residents of the block get to know each other, host community events like block parties and festivals, and look out for each other’s homes. People on a block are most familiar with the patterns and rhythms of that block—more so than police officers.

"INSERT MOBILE SIDEMENU HERE"

But, the local government has a part to play too, and a responsibility to support residents in this role. It can do this by providing tools that facilitate togetherness. These can be digital infrastructure that enables the easy flow of information across the community. Developing mechanisms for identifying potential bad actors and ensuring they are apprehended when necessary—typically the only contact that a community would have with state actors—is also essential. Articles of clothing that differentiate neighbourhood monitors and make them visible to the community at large are a seemingly minor but equally important tool, as are investments in essential infrastructure like lighting and public spaces.

Many people have expressed reservations over this approach. What about the ever-present threat of vigilantism? They ask. What prevents these organised groups from becoming a law unto themselves under the guise of protecting communities? These are valid questions.

For Block Clubs to work, each establishing community needs to create a democratic council. It is a space for sharing information, discussing challenges and problems that arise, a room for accountability. Communities also need to develop specific mechanisms to expose and address misconduct. Misconduct is an offence to the community as a whole—not just to an individual.

The Black Lives Matter Protests sparked by the death of George Floyd and the #EndSARS protests, while in different contexts, amount to the same thing. People are demanding a different approach to how we think about safety. Reducing crime is not something that only cops can do. Other ways exist. Resources that we have long ignored and need to claim back for ourselves.

2020 taught the world that the notion of collective good must be front and centre. Economic, political and social systems based upon individualism and weak public infrastructure continue to devastate communities grappling with the public health crises of disease and violence. Designing systems of care and accountability requires hyper-local efforts that restore the fabric of togetherness—even in an environment where physical distancing may be necessary. Communal safety systems reduce the role of the state, thus limiting the possibilities for state-sanctioned violence. They also position communities to mitigate instances of intercommunal violence through a strong apparatus for monitoring, accountability and the development of safety norms based on the collective good.