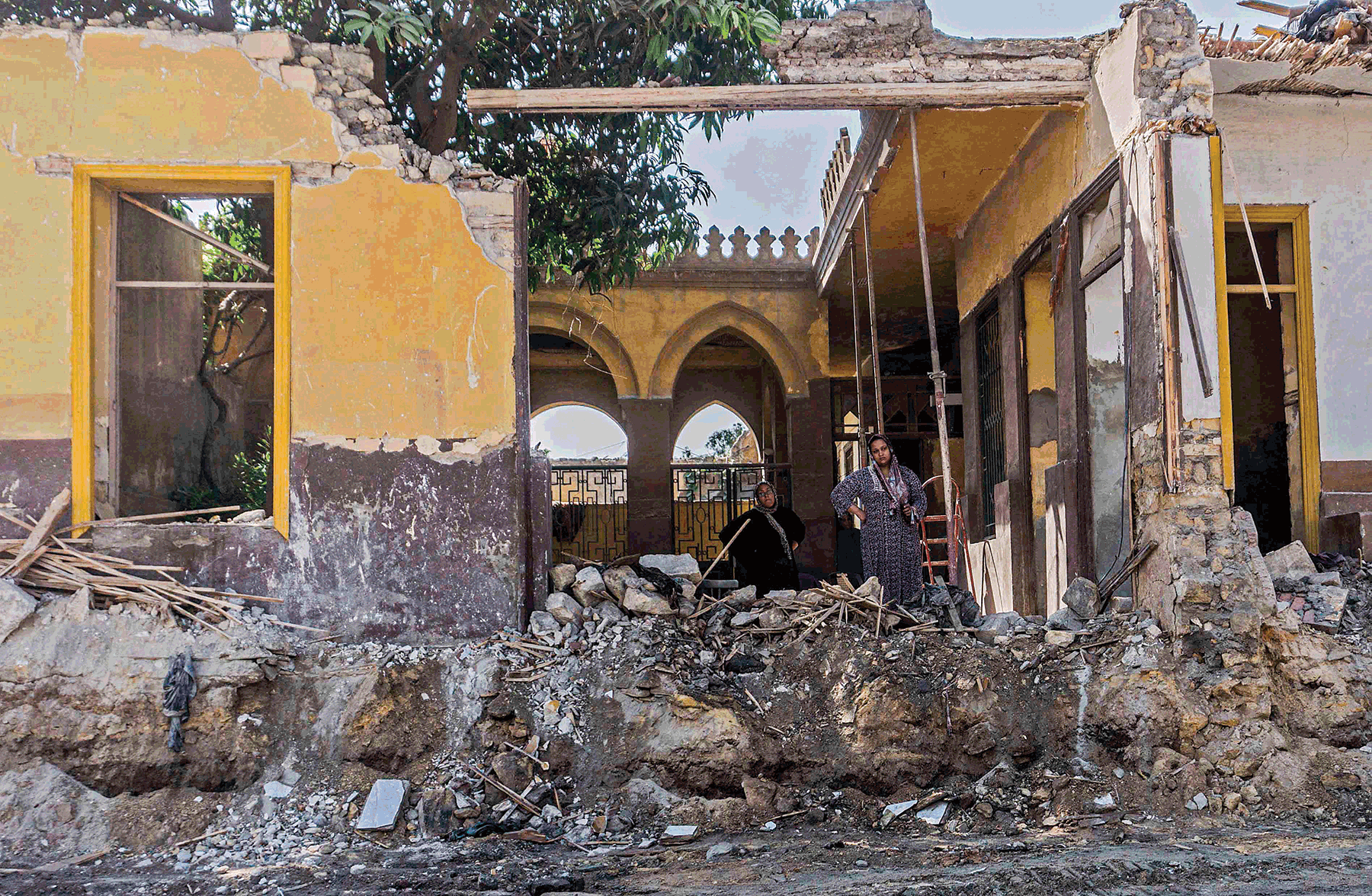

Residents of a cemetery undergoing demolition stand in the rubble amidst ongoing roadworks at the historic City of the Dead necropolis of Egypt’s capital Cairo on July 26, 2020. Photo by KHALED DESOUKI/AFP via Getty Images

Government sanctioned destruction in Cairo

A wave of government demolitions making way for new construction and highway expansion is causing chaos

13 Aug, 2020 | Updated 02 Jul, 2021

In the early hours of June 30, 2020, I received a distressed email from a friend in the US, inquiring about his late father’s grave. My friend fretted about news that the Cairo municipal authority was demolishing graveyards to clear land for an elevated motorway. He worried whether the remains of his father—a renowned physician from Pakistan who died in the 1965 PIA flight 705 crash over Cairo—would be among those destroyed.

By the time I reached the vicinity of Imam Shafe’i graveyards where victims of the crash were buried, bulldozers had already demolished parts of the wall surrounding the memorial cemetery. Construction of

a bridge had begun. I was therefore relieved to find that the bulldozers had spared my friend’s father’s burial spot.

Not long afterwards, another 2,000 family graves were demolished in the City of the Dead. Located both to the north and south of the Cairo Citadel, this enormous cemetery is part of the Historic Cairo World Heritage Site. Here, too, family grave compounds, some dating back more than a century, were bulldozed. Families of the buried were given short notice, and hundreds of caretakers living in the graveyards were evicted. While the demolitions in Islamic cemeteries incited a brief cacophony from heritage conservationists and elites who also stood to lose their family graveyards, the destruction speaks to a larger trend.

Not a day passes without demolitions across Cairo. Cutting of trees, razing of houses and desecration of graves are clearing the way for a frenzy of new construction, highway expansion and roadway bridges, all of which are making calculated incisions into densely populated neighbourhoods.

As the city wades through the latest Covid-19 regulations and related curfews, authorities have taken the opportunity to implement a total ban on private construction, numerous evictions, as well as a declaration to wipe out within two years all unplanned and self-constructed areas—a category constituting 60% of the country’s-built fabric, and 12% of Cairo’s. It is understatement to say that Cairo is in a state of harried confusion.

The city has been in this state since 2016, when the country’s President, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, began waging war on self-built settlements. Deploying a combination of bulldozers and administrative punitive actions, he is also employing what Jordanian architect Hanna Salameh refers to as “weapons of mass construction”.

One such weapon is the programme of ‘unsafe’ areas, which category constitutes 1% of the national built area.

In 2009, the Egyptian government introduced a risk-based classification of informal settlements, pejoratively known in Arabic as ashwai’yat (haphazard). Derived from UN-Habitat’s State of the Worlds Slums - 2005, the classification matrix focused on the structural conditions of buildings, topographical features, utility indicators and tenure status.

Creating four grades of risk, ‘slums’ could be categorised as “life-threatening”, “unsuitable shelter”, “health-threatening” or “insecure tenure”. As such, they could be brought under the Unified Building Law -119/2008- as ‘replanning’ zones, a euphemism for demolition.

"INSERT MOBILE SIDEMENU HERE"

Many experts celebrated the matrix as a practical tool for imagining ‘participatory’ upgrading. International aid agencies flying the ‘inclusive cities’ banner jumped at the opportunity to assist municipal authorities, bringing their expertise to advise on the “highest and best use” of cleared plots.

The programme claiming the eradication of 1% of ashwai’yat was funded by proceeds from selling commercial units developed in place of demolished buildings, surplus profits from urban redevelopment projects, property tax tranches and possibly international donor money. In 2017, after a programme worth EGP1 billion ($64 million), Cairo was declared free of unsafe areas!

The reality is that this ‘objective’ matrix was a trojan horse for slum clearance and forced evictions, ultimately disrupting and destroying countless livelihoods.

Since 2020, the government has gone on a drive to find new ways to increase its revenue base. New ways to levy residents—some conjured from old and forgotten laws, and others newly conceived—have been introduced. Among this arsenal are fines for reconciliation of building violations, a punctuated ban on private construction, and land value capture mechanisms like betterment levies. While these measures oil the mass-construction machine, they also facilitate the attrition of the remaining 99% of unplanned settlements by the sheer burden they place on household budgets.

In less than a year, 15 massive new motorway bridges have risen up over Cairo central, with even more across the Greater Cairo Region. The bridges cut through dense neighbourhoods such as El-Zomor axis, connecting to broader transport corridors surrounding and bypassing the city. Such infrastructure is linked to frantic preparations to finish constructing the aptly named New Administrative Capital. A sprawling new city located about 60km out of Cairo, it is where many of the country’s wealthy, top bureaucrats and international elites will relocate by year’s end. The ongoing activity has turned daily navigation of life in the city and commuting into an epic farce. Road-widening and tree clearing often leave in their wake fatal and hazardous streets.

In small ways, some are fighting back. Ashgarek ya Masr (O! Your Trees Egypt) is one of several Facebook groups that chronicle brutal tree clearances. In a city where nothing is left to waste, the trees chopped up to make way for road-widening projects are sold for profit. Members of groups like Ashgarek ya Masr chronicle this. They also expose how sidewalks and pavements across the city are turned into heaps of debris, effacing popular landmarks and memories along the way.

Like the rest of Egypt, Cairo has been under a national state of emergency since 1958, with intermittent periods of relief, but all the while, largely thriving in its tightly knit and densely populated areas. Ten years after the January 2011 uprising, the city, burdened by its history, seems gripped by a fascination with grandeur, speed and megalomaniac construction. It is almost as if Cairo is determined to wipe out its history by erasing the memories and built fabric representing it.